Practice as Transformation of Consciousness

The idea that our conscious experience is under-lied by an enduring substrate is a natural extension of Mundane Right View and the insight into the selfless nature of the five skandhas. Practically speaking, in the Buddhism of the Nikayas, there is no need for further discussion after the cessation of rebirth at the attainment of arhatship. The world is likened to a house on fire, and the admonition is: get out! There is a clear progression from being caught in cyclic existence to liberation from it, the entirety of which can be expressed with emojis:

🤤 Enchantment with Samsara ->

🫣 Shock at the futility of Samsaric activity ->

😮💨 Recognition of the path ->

😠 Spiritual urgency ->

🥹 Seeking refuge ->

🫡 Observance of precepts ->

😌 Stilling of the mind ->

🧐 Insight meditation ->

😇 Achievement of Nirvana: "Birth is destroyed, the holy life has been lived, what had to be done has been done, there is no more of this state of being."

Later on, however, it was pointed out that a lot of Mundane Right View loses all meaning in the face of the insight of the selfless nature of the skandhas. The Buddha himself taught repeatedly about the unfindability of the self.

Without a self, how can the effectiveness of the views about karma in Mundane Right View be explained? If there is fundamentally no proprietor of karma, no one practicing towards liberation, and no one being liberated, then what the hell is actually happening here? The Yogacarins developed an entire model of practice that can operate without the notion of a separate self. They did this by expanding on the fifth aggregate, consciousness. Let’s get into it.

You are here.

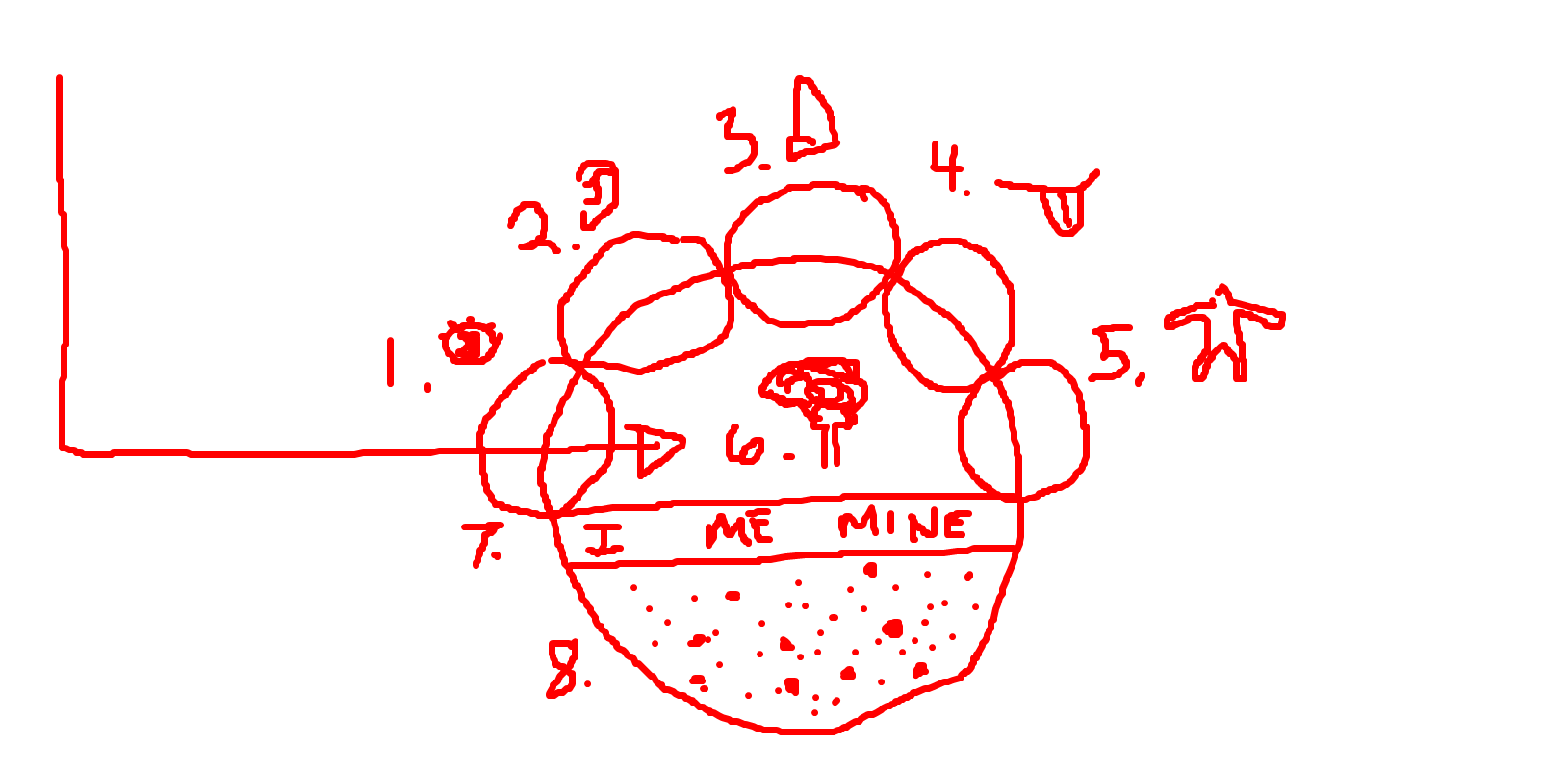

The present moment is the site of the operation of the six sense consciousnesses, the latter-most of which is not the ability to see dead people, but rather the conscious, reflective mind (here called mind consciousness). In addition to these consciousnesses, which are common to the Buddhism of the Nikayas, the Yogacarins added two more layers. The seventh consciousness is called manas and has to do with the functioning of ignorance and self-clinging. I am going to set it aside for the moment. The eighth consciousness is called alaya and is responsible for the maintenance and ripening of karma, i.e. everything that arises in the mind-stream.

Karmic potentials abide as a multitude of seeds, which is why the Chinese translation of alaya uses the character for “store” or “storehouse.” I’ll say store consciousness, but it’s worth noting that alaya is not a container. It is just the totality of the seeds, the way that they condition one another, and the ripening process. I’ll give an overview here in the way that Thay teaches this because he makes it very accessible, but later I will also present the traditional Yogacara account.

When conditions are sufficient, a seed will ripen and manifest in mind consciousness. This can be in conjunction with the operation of a sense consciousness, as when you see a flower in a garden, or solely based on the ripening of seeds into mind consciousness, as when you see a flower in a dream. From this perspective, the answer to the question, “Why is this happening?” Is always the same: because conditions are sufficient. This is the passive aspect of mind consciousness functioning like the space above-ground into which a plant bursts from the soil.

After some time the seed will return to the store to wait again for enough conditions to manifest, but it does not go back unmodified. It will take with it an impression of whatever happened when it was active. In addition, mind consciousness is not only passive. In its active aspect it is the gardener that waters some seeds and refrains from watering others. Thay summarizes this activity as the practice of mindfulness, and presents mindfulness as the chief seed to be watered because mindfulness recollects and sustains the whole gardening process.

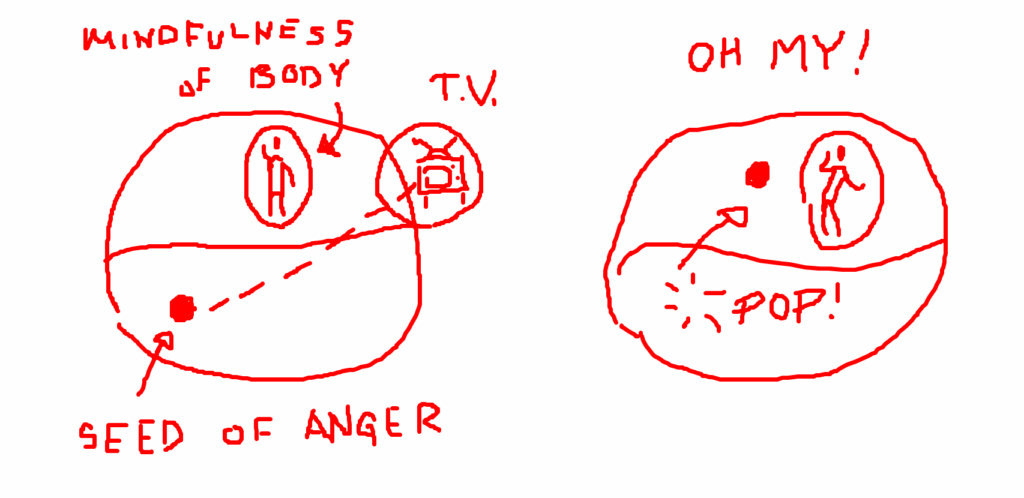

Let’s start with a stripped-down example: a seed of anger has manifested. Maybe you saw something on TV that “made you angry.” But really, the seed has ripened because it is was sown in store consciousness in the past, and conditions are sufficient for it to ripen. Maybe you have watered that seed repeatedly by thinking, speaking, and acting upon anger. What now? In the words of my wonderful teacher, “embrace your anger with mindfulness.”

In order to do this, you’ll need some mindfulness. Early on, you may think that there are times when you don’t need to be aware, or that there is “nothing to practice with.” That mindset is one of the factors of mind to be overcome on the path. It is the opposite of mindfulness, and is called forgetfulness in the Buddhist catalogue of mental formations. There is always something going on. First of all, to put it simply, you are still alive. Without mindfulness there is no way to treasure this fact. Second of all, when afflictions do arise, how long do you want to blunder along before you realize that you need to stop and practice with them? You can only recognize the arising of afflictions when you practice in the absence of afflictions. This also gives you an opportunity to understand the conditions that feed them. The admonition is simple: learn to be at least a little mindful all the time. This is one of the crucial functions of developing the habit of mindfulness of the body. Walk in such a way that you are fully here and you fully recognize that you will never have a chance to take these steps again. Wed your mindfulness to a profound appreciation for what it is like to have a body and to be on this earth, and as long as you have that body, mindfulness will be available when you need it.

If it isn’t obvious from what’s above, mindfulness is not just awareness. It also has the function of recollection, a kind of contextualization of the object of awareness. It recollects “what is going on.” In the example with anger, what is going on? Did something on TV piss you off? Or are you dealing with a mind that has been conditioned to produce anger? The way you answer this question determines your future in the sense that it will shape which seeds get resown in store consciousness. There are two ways that things can go:

| With Mindfulness | With Forgetfulness |

| Anger arises. | Anger arises. |

| Anger is recognized as anger: “Hello my little anger!” | Anger is either not recognized, or recognized as me: “I’m angry.” |

| Anger’s causes are known: “This seed has been watered.” “I didn’t guard my senses.” | Anger’s causes are projected: “They are doing wrong!” “I won’t take this!” |

| Anger’s arising, enduring, and passing away are observed with mindfulness. | Anger is rehearsed through actions of body, speech, and mind. |

| Anger returns to store consciousness weakened and associated with mindfulness. | Anger returns to store consciousness strengthened. |

| Future anger is less likely to arise, less intense when arisen, and easier to practice with. | Future anger is more frequent, more intense, harder to retrain. |

The entire process for the transformation of the mind can be described in terms of the selective watering of seeds: growing wholesome ones, and starving unwholesome ones. In fact, if you remember back to Right Diligence of the Noble Eightfold Path, our scenario slots right in as the second of the four practices.

- Prevent unwholesome dharmas from arising.

- Abandon unwholesome dharmas once arisen.

- Cultivate wholesome dharmas that haven’t yet arisen.

- Maintain wholesome dharmas that have arisen.

These four practices are framed in the language of the Buddhism of the Nikayas. The Buddha does not say to embrace your anger like a mother embracing a crying child. The Buddha says to abandon your anger. This is bad news for your anger if it is a crying child, and brings us to a divergence between the practice approach of Mahayana Buddhism and that of the Nikayas. This is something that Thay doesn’t really talk about, but I think it’s worth bearing in mind if you are exposed to teachings from both traditions.

Remember the two points that I highlighted last week from mundane right view:

- There are beings reborn according to their actions. (Namely you, in each moment.)

- There are good and bad results of karma. (Namely wellbeing or ill-being.)

In our example, regardless of whether or not mindfulness was present, anger still arose. Anger–the affliction which “destroys all the good conduct that has been accumulated over thousands of eons” according to Santideva, and which leads to rebirth into one of the Burning Hells, which have appealing names such as Screaming and Crushing. Is this a problem? The answer is no. The only thing that can engender karma is a volitional act, which is why the underlying thrust of Mundane Right View is to take radical responsibility for your actions. Both traditions are in perfect agreement on this point. In principle there is nothing alarming about having a mind beset by an endless stream of afflictions. Everyone’s mind is like that. The problem comes when, out of ignorance, you identify with those afflictions and act them out in words, thoughts, or deeds. This is the cycle of Samsara that needs to be cut.

But maybe you are alarmed, and you’re saying to yourself, “Good lord! How will I dare to act, tender young practitioner that I am, knowing that wrong actions undertaken in ignorance may lead to rebirth in a place called Great Crushing?” You may be reassured to know that actions principally undertaken out of ignorance will only lead to rebirth in one of the animal realms. But more importantly, it is a special charm of the practice that it is necessarily undertaken conditioned by ignorance. This is why Mundane Right View is provisional. If you could do it perfectly, you would be a Buddha, so please don’t worry too much about this. The important thing is that wholesome efforts, however small and imperfect, accumulate in store consciousness.

The path itself is conditioned. The Buddhism of the Nikayas arose in a certain context. It was a discovery made by wandering renunciants in rural India. It should be no surprise that in early Buddhism everything has a flavor of renunciation. This rings a little of the man who found happiness building birdhouses and became convinced that the practice should be taught in public schools. The traditional approach endures today because it works–if the assumptions are taken seriously and the practices are pursued. Samsara is full of suffering. Escape from it. Sense impressions disturb the mind. Seek seclusion. Beauty is enchanting. Generate revulsion. Intentional acts create karma. Withdraw volition from them. When the shortcomings of samsara are perceived, spiritual urgency arises and you take this as your one and only chance to get the hell out of here. Yes, there is ultimately no “you” that needs to be liberated, but the self-centered ignorance that you are sowing into store consciousness will eventually be overwhelmed by wisdom in deep looking meditation.

In Mahayana Buddhism, you skip a step. Why sow seeds of self-centeredness when you can sow other seeds that are more in accord with the ultimate wisdom that will flow from the meditation process? It doesn’t require supramundane insight to see that the benefits of wisdom and compassion are not constrained by the notion of self and other. If they were, the Buddha wouldn’t have been able to help anyone. But he was. He embodied the wisdom that ends suffering. In Mahayana Buddhism, rather than withdrawing volition, you generate it–a powerful unceasing, red-hot desire: I too will embody that wisdom for the benefit of everyone. This is called Bodhicitta, the supreme virtue to be cultivated, the best friend of mindfulness, the volition that Thay embodies when he says to embrace your anger like a mother embracing a crying child, and the subject of this week’s meditation. Next week, we’ll look at the various wonderful ways that it transforms the seeds in store consciousness. I’ll leave you with a little paraphrase from Santideva, who would like to share with you his view on Bodhicitta, which is translated here as the Spirit of Awakening.

This human existence, which is so difficult to obtain, has been acquired, and brings about the welfare of the world. If I fail to take advantage of it now, how will it ever arise again?

Just as lightning illuminates the darkness of a cloudy night for an instant, in the same way, by the power of the Buddha, occasionally people’s minds incline toward merit.

Thus, virtue is perpetually ever so feeble, while the power of vice is great and dreadful. If there were no Spirit of Perfect Awakening, what other virtue would overcome it?

The Lords of Sages, who have been contemplating for many eons, have seen this alone as a blessing by which joy is easily increased and immeasurable multitudes of beings are rescued.

Those who long to overcome the abundant miseries of mundane existence, those who wish to dispel the adversities of sentient beings, and those who yearn to experience a myriad of joys should never forsake the Spirit of Awakening.

When the Spirit of Awakening has arisen, in an instant a wretch who is bound in the prison of the cycle of existence is called a Child of the Buddha and becomes worthy of reverence in the worlds of gods and humans.

Upon taking this impure form, it transmutes it into the priceless image of the gem of the Conqueror. So, firmly hold to the quicksilver elixir, called the Spirit of Awakening, which

must be utterly transmuted.The world’s sole leaders, whose minds are fathomless, have well examined its great value. You who are inclined to escape from the states of mundane existence, hold fast to the jewel of the Spirit of Awakening.

Just as a plantain tree decays upon losing its fruit, so does every other virtue wane. But the tree of the Spirit of Awakening perpetually bears fruit, does not decay, and only flourishes.

Owing to its protection, as due to the protection of a powerful man, even after committing horrendous vices, one immediately overcomes great fears. Why do ignorant beings not seek refuge in it?

Like the conflagration at the time of the destruction of the universe, it consumes great vices in an instant.

In brief, this Spirit of Awakening is known to be of two kinds: the spirit of aspiring for Awakening, and the spirit of venturing toward Awakening.

Just as one perceives the difference between a person who yearns to travel and a traveler, so do the learned recognize the corresponding difference between those two.

Although the result of the spirit of aspiring for Awakening is great within the cycle of existence, it is still not like the continual state of merit of the spirit of venturing.

From the time that one adopts that Spirit with an irreversible attitude for the sake of liberating limitless sentient beings,

From that moment on, an uninterrupted stream of merit, equal to the sky, constantly arises–even when one is asleep or distracted.

A well-intentioned person who thinks, “I shall eliminate the headaches of sentient beings,” bears immeasurable merit.

What then of a person who desires to remove the incomparable pain of every single being and endow them with immeasurable good qualities?

Who has even a mother or father with such altruism? Would the gods, sages, or Brahmas have it?

If those beings have never before had that wish for their own sake even in their dreams, how could they possibly have it for the sake of others?

How does this unprecedented and distinguished jewel, whose desire for the benefit of others does not arise in others even for their own self-interest, come into existence?

How can one measure the merit of the jewel of the mind, which is the seed of the world’s joy and is the remedy for the world’s suffering?

If reverence for the Buddhas is exceeded merely by an altruistic intention, how much more so by striving for the complete happiness of all sentient beings?

Those desiring to escape from suffering hasten right toward suffering. With the very desire for happiness, out of delusion they destroy their own happiness as if it were an enemy.

He satisfies with all joys those who are starving for happiness and eliminates all the sorrows of those who are afflicted in many ways.

He dispels delusion. Where else is there such a saint? Where else is there such a friend? Where else is there such merit?

Even one who repays a kind deed is praised somewhat, so what should be said of a Bodhisattva whose good deed is unsolicited?

The world honors as virtuous one who makes a gift to a few people, even if it is merely a momentary and contemptuous donation of plain food and support for half a day.

What then of one who forever bestows to countless sentient beings the fulfillment of all yearnings, which is inexhaustible until the end of beings as limitless as space?

The Lord declared, “One who brings forth an impure thought in his heart against a benefactor, a Child of the Buddha, will dwell in hells for as many eons as there were impure thoughts.”

But if one’s mind is kindly inclined, one will bring forth an even greater fruit. Even when a greatly violent crime is committed against the Children of the Buddhas, their virtue spontaneously arises.

I pay homage to the bodies of those in whom this precious jewel of the mind has arisen. I go for refuge to those who are mines of joy, toward whom even an offence results in happiness.